In 1950, the Stewart Center moved locations as a result of racial tensions in it's neighborhood. While this entry explores issues of racism and "white flight," it's purpose is not to place judgement on the Stewart Center's leadership or their decision to move. Rather, it is simply to explore the greater issues that were taking place around them. While I wish I could have been a fly on the wall as decisions were made, I know that the factors of the move were likely more complex than we can know.

______________________________________________________________________________

In 1950, the Andrew P. Stewart Center moved from English Avenue to Reynoldstown. The question has plagued me since I began delving into the Center's history: why, after 34 years in the English Avenue community, did the Center uproot and move across town? All of my research and reading has produced a two word explanation:

"Owing

to city growth and community changes, the Atlanta Baptist W.M.U. Association

felt the need to relocate the Good Will Center.

Already the churches in the community had relocated."

This vague, unsatisfying rationale begs for more detail. Due to the time period and details regarding the sale of the Pelham buildings, I immediately assumed that the phrase "community changes" was referring to neighborhood desegregation and white flight. We know that the Center sold it's buildings on Pelham street to African American residents, further supporting our concept of the nature of the "community changes" occurring in the English Avenue neighborhood.

"The

Chapel-Recreation Building was sold to the St. James Negro Baptist Church. The main building was sold for a negro

apartment house."

______________________________________________________________________________________

I recently began reading a book called "White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism" by Kevin M. Kruse. What I've learned so far has been very interesting and incredibly relevant to the Center's history.

On Atlanta's west side, Joseph E. Lowery Blvd runs north/south for nearly 3.5 miles. Originally named Ashby Street, this road forms the western border of the present day English Avenue neighborhood, where the Center called home for 34 years.

As it turns out, Ashby Street saw some of the earliest neighborhood racial transitions in the city of Atlanta.

"Just to the east stood the Ashby Street region, which had grown rapidly during the previous decades, emerging as one of Atlanta's most overcrowded black neighborhoods. Indeed, by the 1940's nearly 40 percent of the city's black population lived there, making the enclave's name synonymous with 'black Atlanta.'...The end of World War II brought a severe housing crisis to Atlanta, as thousands of veterans returned home to discover the city had not only failed to build new homes during their absence but actually started to destroy old ones. Black leaders banded together to create new housing on the city's outskirts, but found such projects blocked by local resistance and government red tape. In the end, they had only one option. 'Following the pressure of increased population,' Atlanta's Metropolitan Planning Commission observed, 'their only avenue for expansion has been 'encroachment' into white neighborhoods adjoining their own areas of concentration.'

Logically, the bulk of the early years of black 'encroachment' emerged from the most significant 'area of concentration,' Ashby Street."

In addition to giving us more information about Ashby street and the environment surrounding the Center in the late 1940's, it also tells us that it was among the

first neighborhoods to transition in the city of Atlanta. "White Flight" had not yet begun on a large scale, as this was one of the very first areas to deal with the issue of neighborhood desegregation.

It is reasonable to believe that most (if not all) of the

children who attended the Center would have left the neighborhood during this transition. As long time families left the neighborhood, the Center lost the people it had served for over 30 years. Did the leadership of the Stewart Center reach out to African American families in English Avenue before deciding to move? We don't know.

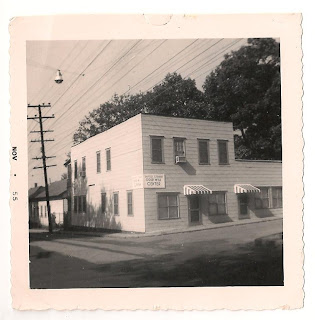

"Mrs. S.D. Katz was appointed

chairman for the committee for the relocation of the Good Will Center. A grave responsibility rested upon her. The task was not an easy one. Mrs. Katz worked faithfully and with the aid

of the missionaries diligently combed the city for the right location. There was much to be considered. The committee after much prayer and

deliberation, felt the directed guidance to this, our present location, 153

Stovall Street, S.E. Occupancy took

place January 1950."

The

written histories of the Center do not give any information about

why

Reynoldstown was chosen for the next location, but demographic data shows that in

1950, Reynoldstown was inhabited by almost exclusively white residents. (Which is interesting, considering Reynoldstown was founded by freed slaves after the civil war---but that's a subject for another blog!) Little did they know, they would be faced with a similar neighborhood demographic change a little over a decade later.

Regardless of the motives and rationale behind the Center's move in 1950, the leadership made a very different decision 15 years later when African Americans began moving into Reynoldstown.

To be continued.

.jpg)

.jpg)