Elizabeth Carolyn Lundy and Myrtle Carolyn Salters served as the missionary directors of the Stewart Baptist Goodwill Center for almost 40 years, from 1935 until 1974. Throughout their tenure, Miss Lundy and Miss Salters loved thousands of children and guided the Center through decades of social change. Day in and day out, the two women devoted themselves to children through nursery care, boys and girls clubs, bible studies, Vacation Bible School, counseling, music, and more. Considering their devotion and their impact, It is only appropriate, then, to take a closer look at their lives before, during, and after their time at the Stewart Center.

Both Elizabeth and Myrtle came from rural upbringings. The older of the two women, Myrtle Salters was born on November 5, 1905 in Johnston, South Carolina, (near Aiken). Her father, George, was a farmer, and it is likely that Myrtle spent her childhood contributing to the daily operations of the farm. She developed an early appreciation for music, learning to play the family pump organ by ear. Elizabeth Lundy was born on August 7th, 1909, and was raised in Sylvester, Georgia. Her father owned a general store, and her family also operated a farm. She graduated from Lumberton High School.

Both women studied to be teachers at all-female, Baptist colleges. Elizabeth attending Bessie Tift College for two years (today, a part of Mercer University). She would later earn her bachelors degree from University of Georgia through summer and correspondence courses. Myrtle attended Coker College, where she earned her bachelor's degree. Upon finishing her studies, Myrtle taught in public schools from 1929-1933 in Cowpens and Cassett, South Carolina and Scottdale, Georgia. It does not appear that Elizabeth taught school after completing her degree.

Elizabeth and Myrtle first met as students at the WMU Training School in Louisville, Kentucky, where they were roommates. It was here that a life-long friendship was born. Often described as opposites due to their markedly different personalities, Myrtle and Elizabeth perfectly complimented one another. Although they couldn't have known it at the time, they would live and work side by side for the next 60 years.

While Myrtle and Elizabeth were students at the WMU training school, they took classes related to theology, evangelism, and social work and practiced music, sewing, and stenography. In addition, all students gained practical experience through field work at local missions in Louisville.

Both Elizabeth and Myrtle worked at the Union Gospel Mission in Louisville as a part of their field work at the WMU Training School. There, Myrtle served as a Recreational Leader, and Elizabeth as a nurse.

Myrtle completed her MRE (Masters of Religious Educaiton) at the training school in 1934 with hopes of being a foreign missionary to China. Upon completing her BRE (Bachelor of Religious Education) at the training school, Miss Lundy was called to Atlanta to serve as the Center's Director in 1935.

"With the beginning of each New Year, my memory goes back to January the first 1935 when I arrived in Atlanta by train and was met at the station by Mrs, John R. Dickey, Supervisor of the Andrew-Frances Stewart Good Will Center.

It was Mrs. Dickey who had first contacted me about accepting the position as Director of the Center. She took me to the Center upon my arrival in Atlanta in 1935 where I never dreamed that my term of service would terminate only when I reached retirement."

While Myrtle waited for clearance to travel to China, she came to Atlanta where she boarded and volunteered alongside her friend Elizabeth at the Goodwill Center, then located at 816 Pelham Street. She also found work as a substitute teacher in Atlanta Public Schools during this time. However, health problems would eventually prevent Myrtle from becoming a foreign missionary. After several years as an unofficial, unpaid volunteer, Miss Salters was hired as Assistant Director and paid a small salary.

For the first 15 years that Elizabeth and Myrtle worked at the Stewart Center, it was located at 816 Pelham Street, in an area often referred to as Bankhead (today known as the English Avenue neighborhood). The Stewart Center was housed in a large, brick building, located only a few yards away from Kingsbery Elementary School. Miss Lundy was active in the PTA at Kingsbery, and the Center had a good relationship with the school. Many of the children living in this neighborhood were children of mill workers who were employed by the Exposition Cotton mills nearby.

In 1949, due to neighborhood changes (black families began moving into the previously white community, leading to Kingsbery Elementary to be "rezoned" as a school for African American children) the WMU felt that the Center needed to be relocated. There was a severe housing crisis in Atlanta at this time, especially for African Americans. As a result, many black families began to purchase homes in adjacent white communities, which caused rapid "white flight" out of the community.

After an extensive search, the WMU located a property at 153 Stovall Street. A former grocery store and apartment house, the building required extensive renovations before it could be opened for children. Miss Lundy and Miss Salters moved into the upstairs apartment, where they would live for the next 24 years. While renovations were taking place, the two women spent several months meeting their neighbors and conducted a "census" to learn more about the community. When the day nursery opened in that fall, several children who attended the Pelham Street Center came from the Bankhead area in order to attend, in addition to children living near the new Stovall Street Center. The recreation/chapel building was constructed a year later.

During their four decades of service, Elizabeth and Myrtle ran the day to day operations of Stewart Center. They kept meticulous records of attendance, baptisms, bibles given to children, etc. The women (Myrtle, in particular) took many photos, and had a small dark room at the Center where Myrtle developed the pictures. Their divergent gifts and personalities suited the women for different roles at the Center.

Myrtle is often remembered for her humor and quick wit, and her light-hearted demeanor. She often worked with the boys at the Center, and grown men remember her lessons in woodworking and fishing trips. Both men and women remember her creativity, and some still treasure the crafts they made with her at the Center. Miss Lundy was more reserved and serious in demeanor and generally worked with the girls, including the GA program. As she was technically the Director of the Center (with Myrtle as her Assistant), Elizabeth was responsible for all that took place at the Center, and took her job very seriously. As evidenced by her later writings and the memories of those who knew her, Elizabeth cared very deeply about the children and the Center, despite her outwardly stern demeanor.

For a 1960 WMU meeting, Miss Lundy and Miss Salters composed a poem about their day to day life at the Stewart Center:

The days are long, the service sweet,

guiding paths for little feet.

We see them run, and sometimes fall,

While joining in a game of ball.

We count for races, break up a fight,

And coming between, we make things right.

We watch the younger ones blow bubbles,

And listen to the old folks' troubles.

We see the poor and hungry fed,

We gently tuck the tots to bed.

We see some born, and watch some die,

We hear some laugh, while others cry.

For the many problems we have to face,

We are undergirded by "sufficient grace"

And, oh, the joy that comes in serving,

We often feel so undeserving!

That God has let us work this long,

And kept us healthy, well and strong.

For the first 15 years that Elizabeth and Myrtle worked at the Stewart Center, it was located at 816 Pelham Street, in an area often referred to as Bankhead (today known as the English Avenue neighborhood). The Stewart Center was housed in a large, brick building, located only a few yards away from Kingsbery Elementary School. Miss Lundy was active in the PTA at Kingsbery, and the Center had a good relationship with the school. Many of the children living in this neighborhood were children of mill workers who were employed by the Exposition Cotton mills nearby.

|

| The Stewart Center at 816 Pelham Street |

After an extensive search, the WMU located a property at 153 Stovall Street. A former grocery store and apartment house, the building required extensive renovations before it could be opened for children. Miss Lundy and Miss Salters moved into the upstairs apartment, where they would live for the next 24 years. While renovations were taking place, the two women spent several months meeting their neighbors and conducted a "census" to learn more about the community. When the day nursery opened in that fall, several children who attended the Pelham Street Center came from the Bankhead area in order to attend, in addition to children living near the new Stovall Street Center. The recreation/chapel building was constructed a year later.

During their four decades of service, Elizabeth and Myrtle ran the day to day operations of Stewart Center. They kept meticulous records of attendance, baptisms, bibles given to children, etc. The women (Myrtle, in particular) took many photos, and had a small dark room at the Center where Myrtle developed the pictures. Their divergent gifts and personalities suited the women for different roles at the Center.

Myrtle is often remembered for her humor and quick wit, and her light-hearted demeanor. She often worked with the boys at the Center, and grown men remember her lessons in woodworking and fishing trips. Both men and women remember her creativity, and some still treasure the crafts they made with her at the Center. Miss Lundy was more reserved and serious in demeanor and generally worked with the girls, including the GA program. As she was technically the Director of the Center (with Myrtle as her Assistant), Elizabeth was responsible for all that took place at the Center, and took her job very seriously. As evidenced by her later writings and the memories of those who knew her, Elizabeth cared very deeply about the children and the Center, despite her outwardly stern demeanor.

|

| Atlanta Constitution Article, September 30, 1956 |

The days are long, the service sweet,

guiding paths for little feet.

We see them run, and sometimes fall,

While joining in a game of ball.

We count for races, break up a fight,

And coming between, we make things right.

We watch the younger ones blow bubbles,

And listen to the old folks' troubles.

We see the poor and hungry fed,

We gently tuck the tots to bed.

We see some born, and watch some die,

We hear some laugh, while others cry.

For the many problems we have to face,

We are undergirded by "sufficient grace"

And, oh, the joy that comes in serving,

We often feel so undeserving!

That God has let us work this long,

And kept us healthy, well and strong.

In the mid to late 1960's, Myrtle and Elizabeth began to see changes in the neighborhood surrounding the Stewart Center, similar to those in English Avenue less than 15 years earlier. This time, rather than moving the Center, Miss Lundy and Miss Salters chose to invite all neighborhood children, regardless of their skin color, to the Stewart Center. "...the two missionary-directors have proved themselves to be sensitive to the needs of a changing community. The solution seemed to lie, not in moving the location but in initiating plans and methods to face the new challenge brought about by the changing community." In 1968, Michael Manuel was the first African American child to attend.

In 1974, after 39 years of service, Myrtle and Elizabeth felt that it was time to retire. Using the language of the stage, Myrtle Salters eloquently described her feelings about retirement:

"As in all performances, sooner or later each player must make his exit in order that another may have a turn. It is with mixed emotions and reluctancy that I must admit it is time for me to step aside. This is not to say that I feel the "performance" is over, or that a climax has been reached, but that my exit is due, effective in the summer of 1974. However, I shall be watching and praying as "the play" goes on--hopefully for many years to come, resulting in countless multitudes being drawn to the Saviour."

Upon retirement, Miss Lundy and Miss Salters were honored at a number of events, including events at First Baptist Church of Atlanta, where they were members, as well as at Second Ponce de Leon Baptist. At their last meeting with the Atlanta WMU, they recited a poem together, which they had written about their lives at the Stewart Center. The closing stanza of the poem reads:

So our memories are happy, our hearts are filled

In knowing we have served where God has willed,

Being victims of both time and age the moment arrived to exit the stage.

We are in His hands His will to do

Through the days ahead He will see us through.

Nearly forty happy years really passed in a jiffy

Makes us almost wish we had worked for fifty.

The WMU presented the women with a large financial gift, which enabled Myrtle and Elizabeth to buy a car. They moved to an apartment in Decatur (1520

Farnell Court), where they lived for 13 years among other retired missionaries. Elizabeth and Myrtle stayed in touch with subsequent directors of the Stewart Center, and visited from time to time.

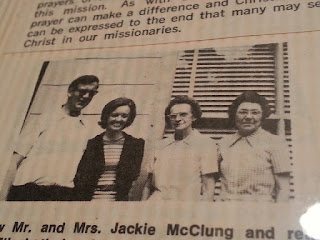

Novella and Jackie McClung, the husband and wife missionaries who were hired following Myrtle and Elizabeth's retirement, recalled that the two women had a difficult time leaving the Center--- particularly Miss Lundy. Novella recalled a visit from Miss Lundy and Miss Salters that occurred shortly after the interior of the Center had been painted. In an attempt to stretch their budget, Novella and Jackie had purchased "rejected" paint from the store, including purple paint that they used for the largest classroom. Upon seeing the room, Miss Salters broke into laughter and Miss Lundy burst into tears.

When Emory University purchased the apartments where Myrtle and Elizabeth lived for student housing in 1987, the two moved to the Baptist Village in Waycross, Georgia. As they continued to age into their 80's, the women received many visits from children, parents, and WMU members who knew them from the Stewart Center.

"The Lord has been/is so good to let us see a few fruits from the seed we had the privilege of planting. We heard via cards, letters and phone calls from some of our former people. July 2-3 I had two of our former children visit me. One attended the Stewart Baptist Center in the 1930's. The other girl went in 1940's. This was their first trip to Baptist Village. They were just bubbling over with happy memories of their days at Stewart Center. One had kept her certificates from V.B.S. and brought them for me to see."

So our memories are happy, our hearts are filled

In knowing we have served where God has willed,

Being victims of both time and age the moment arrived to exit the stage.

We are in His hands His will to do

Through the days ahead He will see us through.

Nearly forty happy years really passed in a jiffy

Makes us almost wish we had worked for fifty.

|

| Elizabeth and Myrtle with Ford Chance and Donnie Watkins at a retirement celebration in their honor. |

|

| Myrtle and Elizabeth with Jackie and Novella McClung. The McClungs served as the new missionary directors of the Center following Elizabeth and Myrtle's retirement. |

When Emory University purchased the apartments where Myrtle and Elizabeth lived for student housing in 1987, the two moved to the Baptist Village in Waycross, Georgia. As they continued to age into their 80's, the women received many visits from children, parents, and WMU members who knew them from the Stewart Center.

"The Lord has been/is so good to let us see a few fruits from the seed we had the privilege of planting. We heard via cards, letters and phone calls from some of our former people. July 2-3 I had two of our former children visit me. One attended the Stewart Baptist Center in the 1930's. The other girl went in 1940's. This was their first trip to Baptist Village. They were just bubbling over with happy memories of their days at Stewart Center. One had kept her certificates from V.B.S. and brought them for me to see."

Myrtle Salters passed away on June 4, 1994 at age 88. In a letter written two months later, Elizabeth remembered her friend and gave thanks for her life:

"I of course miss Myrtle but I do not grieve for her, so thankful she [is] with the Lord. Most of the people at Baptist Village did not know the real Myrtle. She continued to have a smile most of the time, a twinkle in her eyes, and was witty. She did very little talking after being moved to Hall 5--confused more when she talked-- but one day on Hall 6- when the nurse put her arms around Myrtle- was loving her- I said "Myrtle, I believe they are spoiling you" --the quick reply: "Do I smell?"

Upon her death, Myrtle was buried in the Phillipi Baptist Church cemetery, the church in which she was raised in Johnston, SC. Even in 2015, the church proudly remembers Myrtle's lifelong missionary service on their website.

|

| When Myrtle passed away in 1994, Elizabeth with Myrtle's niece Barbara, donated chimes to the Village in her memory. Click the image to read the article. (Courtesy of Ford Chance) |

Elizabeth Lundy outlived Myrtle by 7 years, and passed away on October 17, 2001. She was buried with her family at the Hillcrest Cemetery in Sylvester, Georgia.